Up until the early 20th century horses were the power used for land transport of goods and passengers

I had to drive to west London recently. The journey was without incident until I found myself in a slow procession of cars queuing alongside Gunnersby Park, on the North Circular Road. I was waiting in stationary traffic when my attention was drawn by a sudden flash of white, which had appeared in the corner of my eye from the bottom of a tarmac road on my left. I turned to look and see what it was that had attracted my attention, and through a wooden five-bar gate at the bottom of a long driveway I could see someone exercising a large snow-white horse. I was a little taken aback as, although the area is generally affluent, I really hadn’t expected to see a horse in such a built up area. It was then that I realised I was actually looking into an exercise arena of the Ealing Riding School, which is one of a number of riding establishments within the capital. A large sign at the entrance to the drive offered ‘free manure or compost. Bring your own bags and tools.’

Great Manure Crisis of 1894

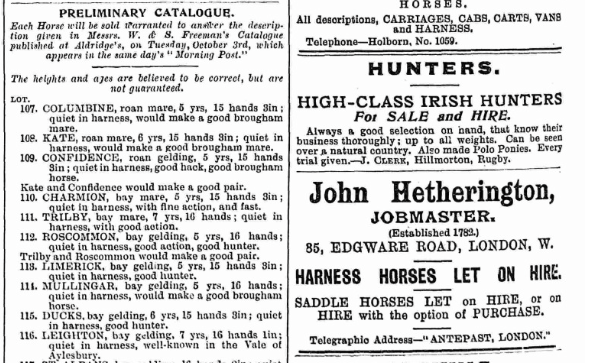

The sign got me thinking about an article I had read a while ago about the hysteria at the end of the nineteenth century regarding the abundance of manure that was being produced by London’s many thousands of working horses. In 1894 the London Times estimated that by 1950 every street in the capital city would be buried to a depth of nine feet in horse manure. The ‘Great Manure Crisis’ was basically the environmental emergency of its day. Of course, at that time real horsepower conveyed all transport on land, whether of goods or passengers. At the dawn of the twentieth century London had approximately 11,000 licensed horse-drawn cabs and thousands of ridden horses, carts, wagons, packhorses and drays going about their business every day. The thousands of omnibuses that operated daily, for instance, each required a total of up to 12 horses, working in three to four hour shifts of two horses per shift, which added to the accumulation of organic waste material. The consequence of all this manure was the presence of large numbers of flies, unpleasant odours, deep mires in the winter, and dung-dust in the summer. Gangs of men, known as ‘sparrow starvers’, would sweep certain streets clear of manure and collect payments in the fashion of modern-day ‘squeezie-merchants’.

The Sparrow Starver

It was the widespread adoption of motorised transport in the early part of the twentieth century that saw working horses rapidly replaced on the streets of London. In 1900, for example, there were no licensed motorised cabs in London but by 1910 there were 6397. Although the birth of the modern motorcar is generally accepted to have been in 1886 and credited to Karl Benz, in Germany, the new method of transport would not become widely available until after Henry Ford, in the USA, had introduced assembly-line processes in 1908. Suddenly it was the turn of the motorcar to be nicknamed ‘the sparrow starver’. In modern-day London the streets are now clear of horse-muck and the great manure crisis of 1894 is just a curious episode in urban history. However, along with the disappearance of horse-dung went the presence of the little bird most closely associated with the capital city. Today the almost total absence of the ‘cockney sparrah’ in London is much lamented by conservationists and ornithologists alike. Thankfully sparrow numbers in the New Forest are doing well, according to regular surveys and sightings, by organisations such as the RSPB and local natural history groups. This, of course, is because of the remarkable biodiversity of the Forest is achieved under the influence of the commoning livestock, which graze and browse the shrubs and grasses, depositing their droppings on the landscape. Gardeners have long testified to the beneficial effects of horse-manure on roses but, it would seem, that equine waste-matter has other important ecological benefits too.

The biodiversity of the New Forest is achieved under the influence of the commoning livestock.

You must be logged in to post a comment.