In the nineteenth century the New Forest woods were prone to ‘modern Vandalism’.

In 1871 George Briscoe Eyre, the owner of the Bramshaw (or Warren’s) Estate, wrote that’ although a nation of tourists, the English are strangely apt to overlook the claims of their own country upon their attention and its exceptional variety of atmosphere, contour, and vegetation’.[1] He expressed no surprise, therefore, that a district like the New Forest should be comparatively little known, and its value to the nation in general, whether from an aesthetic or an economical point of view, be imperfectly recognised. Perhaps it was this ‘out of sight, out of mind’ state of affairs that had caused the Forest landscape during the mid-nineteenth century to lose several thousand acres, which were cleared, enclosed, and planted with soft woods, such as Scotch pine, at the sacrifice of some of its grandest old woods, and the wild picturesque beauty of whole districts.[2] In a policy described as ‘modern Vandalism’, Eyre describes how the old beech trees were felled and sold for firewood; the dimpled hollows, bared of their trees, were scored with parallel trenches; the winding streams straightened; and a dull monotony of fir plantation ‘will soon cover, with a not unkindly mantle, the last traces of ruined beauty’.[3] The surveyor, he believed, had undone the work of the artist, and replaced with hard outlines the soft irregularity of Nature.

Attempts to separate the commoners from the Forest

But the ancient landscape and ornamental trees were not the only features of the New Forest to be marked for destruction during this time. In December 1853, the Deputy Surveyor had written to the Chief Commissioners of Woods stating, ‘It appears to me to be important that the Crown should as soon as possible exercise its right of enclosing the 16,000 acres, because, exclusive of other advantages, by doing so all the best pasture would be taken from the commoners and the value of their rights of pasture would be materially diminished, which would be of importance to the Crown in the event of any such right being commuted.’[4] Later giving evidence before a Select Committee in 1875, Kenneth Howard, Commissioner of Woods, was asked about this policy and answered that rather than repudiating the statement in the letter he regretted that it had ever been made public. Indeed, he believed the sooner common rights were separated from the Forest the better.[5] While Briscoe Eyre believed that ‘the most intelligible and indisputable proof of the value of open spaces and common rights’ was the comparative absence of pauperism in the region.[6] The end of the nineteenth century represented a challenge to the Crown’s priorities for the New Forest.[7] Local and national campaigns to preserve the Forest, after the revelations of the Select Committee, culminated in the New Forest Act 1877, which laid the foundations for its contemporary management. Today commoning is recognised more for its contribution to the biodiversity of the New Forest landscape and its heritage value in sustaining traditional practices, which contribute towards a thriving tourist economy. Far from being ‘imperfectly recognised’ the New Forest is now the most visited National Park in the county. I wonder what Briscoe Eyre would think of that?

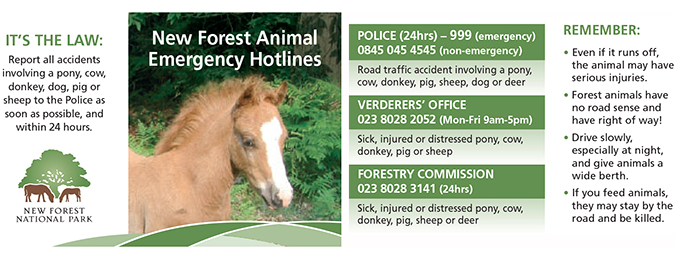

The practice of commoning, which has existed uninterrupted for over a thousand years, is still the dominant influence over the Forest’s ecology, economy and community.

Sources:

[1] G. E Briscoe Eyre, ‘The New Forest: A Sketch’ in The Fortnightly Review, Volume. IX, January 1 to June 1, 1871 (London, 1871), p. 433.

[2] Ibid, p. 434.

[3] G. E Briscoe Eyre, The New Forest: Its Common Rights and Cottage Stock-Keeper (Lyndhurst, 1883), p. 12.

[4] Eyre, 1871, p. 447.

[5] Eyre, 1883, p. 30.

[6] G. E Briscoe Eyre, The New Forest: Its Common Rights and Cottage Stock-Keeper (Lyndhurst, 1883), p. 52.

[7] Victoria M. Edwards, ‘Rights Evolution and Contemporary Forest Activism in the New Forest, England’, in Thomas Sikor and Johannes Stahl (eds.), Forests and People: Property, Governance, and Human Rights (Abingdon, 2011), p. 135.

You must be logged in to post a comment.