Dame Alice Lisle lived in the New Forest during the troubles of the seventeenth century.

The 2nd September marked the anniversary of the death of Dame Alice Lisle. She was the last woman to be executed by a judicial sentence of beheading in England, and died in early September 1685, at the age of 68. Her alleged crime was of harbouring fugitives at her home in Moyles Court after the disastrous Monmouth Rebellion, which ended with the Battle of Sedgemoor. The Monmouth Rebellion was an attempt by the illegitimate son of Charles II to overthrow his uncle James II. James II had converted to Catholicism and the Duke of Monmouth, being a protestant, felt that this gave him a better claim to the throne. Monmouth’s small army was poorly trained and ill equipped for fighting against the professionally trained and seasoned royal army. During the Battle of Sedgemoor, as soon as it became apparent that his army was being defeated, Monmouth fled towards the coast with the aim of making for the continent. He was found, after a tip-off, hiding in a ditch near Verwood disguised as a peasant. He was arrested and later executed on Tower Hill, in July 1685. In the meantime, other rebels fled the battle scene. John Hickes, a well known Non Conformist Minister, and Richard Nelthorpe, a lawyer who carried the taint of outlawry, sought shelter with the widowed Lady Lisle in her New Forest home. The following morning, after another tip-off, the two men were arrested and Lady Lisle was charged with aiding the traitors.

Judge Jeffreys – ‘The Hanging Judge’

The trial judge during Lady Lisle’s court case was the notorious Judge Jeffreys, known as ‘The Hanging Judge’, who had a reputation for severity and prejudice. From the outset it is clear that he considered the unfortunate lady guilty. Her defence was that she had not known that the men had been party to the Monmouth Rebellion; she had thought that they were in trouble for preaching illegally. She pleaded her innocence and declared that she had no sympathies with the rebellion. Judge Jeffreys, however, refused to believe her. Because she had been married to one of the men who had organised the trial of Charles I and had overseen his regicide, Jeffreys concluded that she must be a traitor. Judge Jeffreys therefore bullied the reluctant jury into finding the old lady guilty. The jury were said to have found Lady Lisle ‘Not Guilty’ three times and each time Judge Jeffreys sent them out again. Only when he threatened them with ‘an attaint of treason’ did they find her guilty. He expressed surpise at the jury saying; “I did not think I should have had any occasion to speak after your verdict, but finding some hesitancy and doubt among you, I cannot but say, I wonder it should come about; for I think in my conscience the evidence was as full and plain as could be, and if I had been among you, and she had been my own mother, I should have found her guilty”.[1] James II commuted her sentence, of burning at the stake, to beheading in deference to her rank and she duly lost her life on a public scaffold in Winchester, opposite the Eclipse Inn. Moyles Court, the scene of the alleged crime, stills exists and is now a thriving school. There is also a pub and restaurant nearby named in her honour. Her shade is said to haunt the vicinity, where she is often conveyed in a spectral coach pulled by headless horses, or the crunch of its wheels can be heard on the gravel tracks at night. As a result of her treatment many writers have described Lady Alice Lisle’s execution as a judicial murder and she is also regarded as the first martyr of the Bloody Assizes.

The shade of Alice Lisle is said to ride in a phantom coach. The crunch of its spectural wheels can be heard on the Forest tracks.

[1] T. B. Howell, A Complete Collection of State Trials, Vol. XI (London, 1816), p. 374.

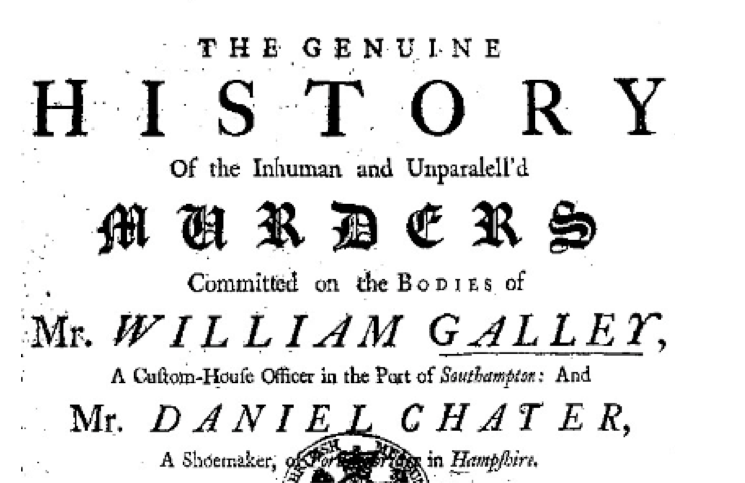

In 1747 a gang of smugglers decided to go over to Guernsey to buy quantities of tea, which on their return to England they could sell for a profit. In their number was one John Diamond, otherwise known as Dymar, who would became a central figure in the unfortunate events that later unfolded. On their return to Christchurch Harbour they were intercepted by a revenue vessel, which patrolled the English Channel to apprehend ‘free-traders’ and seize their goods. Though the smugglers were able to escape on a small boat, their vessel and the contraband it contained was impounded at Poole Custom House. In an act of incredible audacity the gang later attacked the Custom House and stole back their booty. On their way to commit this crime the smugglers had travelled through the New Forest, where they had stayed the night, before making their way to Poole. They had made no secret of their plans and so as they returned with their illicit goods they were met with popular acclaim. Many smugglers were seen as Robin Hood-type characters or ‘honest rogues’ who were fighting what the general populace saw as unfair taxes on luxury goods. By the time the gang reached Fordingbridge people were in the streets cheering and waving to them. John Diamond riding high on his horse saw in the crowd an old acquaintance, Daniel Chater, who was a shoemaker in the town. The pair had worked together during the harvest season and were well-known to each other. Diamond threw Chater a bag of tea as he passed by and rode on with the gang. In that moment of casual acknowledgement and boastful largesse the fate of both men were sealed.

In 1747 a gang of smugglers decided to go over to Guernsey to buy quantities of tea, which on their return to England they could sell for a profit. In their number was one John Diamond, otherwise known as Dymar, who would became a central figure in the unfortunate events that later unfolded. On their return to Christchurch Harbour they were intercepted by a revenue vessel, which patrolled the English Channel to apprehend ‘free-traders’ and seize their goods. Though the smugglers were able to escape on a small boat, their vessel and the contraband it contained was impounded at Poole Custom House. In an act of incredible audacity the gang later attacked the Custom House and stole back their booty. On their way to commit this crime the smugglers had travelled through the New Forest, where they had stayed the night, before making their way to Poole. They had made no secret of their plans and so as they returned with their illicit goods they were met with popular acclaim. Many smugglers were seen as Robin Hood-type characters or ‘honest rogues’ who were fighting what the general populace saw as unfair taxes on luxury goods. By the time the gang reached Fordingbridge people were in the streets cheering and waving to them. John Diamond riding high on his horse saw in the crowd an old acquaintance, Daniel Chater, who was a shoemaker in the town. The pair had worked together during the harvest season and were well-known to each other. Diamond threw Chater a bag of tea as he passed by and rode on with the gang. In that moment of casual acknowledgement and boastful largesse the fate of both men were sealed.

You must be logged in to post a comment.