The New Forest is loved for its scenery, wildlife and the free roaming animals.

While visitors to the New Forest, and those lucky enough to reside here, undoubtably appreciate its magnificent scenery, free roaming livestock, and exceptional wildlife, not many would consider the significance to the landscape of the unbroken chain of Forest ancestry that occurs in some of the commoning families. Several of these families span generations that are as old as the oaks and beech trees that make up the ancient woodland. It is tempting to imagine that some may even pre-date the creation of the New Forest in the late 11th century, and to have been resident in these parts when the Saxons referred to the territory as Ytene. To me, the preservation of these human markers of heritage is just as important as protecting the landscape they have nurtured, and been nurtured by, for centuries. Indeed, some writers have described the relationship between the commoners and the New Forest as symbiotic, meaning that effectively one cannot live without the other, which, in my humble opinion, is undoubtedly true. The commoners know the Forest intimately. Scientists examining the Forest’s habitats have often confirmed, using ‘painstaking quantification’ or rigorous scientific method, what has been in the knowledge of generations of commoners. In fact, how many times do we reflect upon the innate skill or abilities of certain people and remark ‘”it’s in their blood”? Long have I suspected, therefore, that many of my commoning friends have inherited memories (and wisdom) about the landscape from their ancestors, as well as the colour of their hair and eyes, shape of their bodies, or height, and so on.

Commoning families

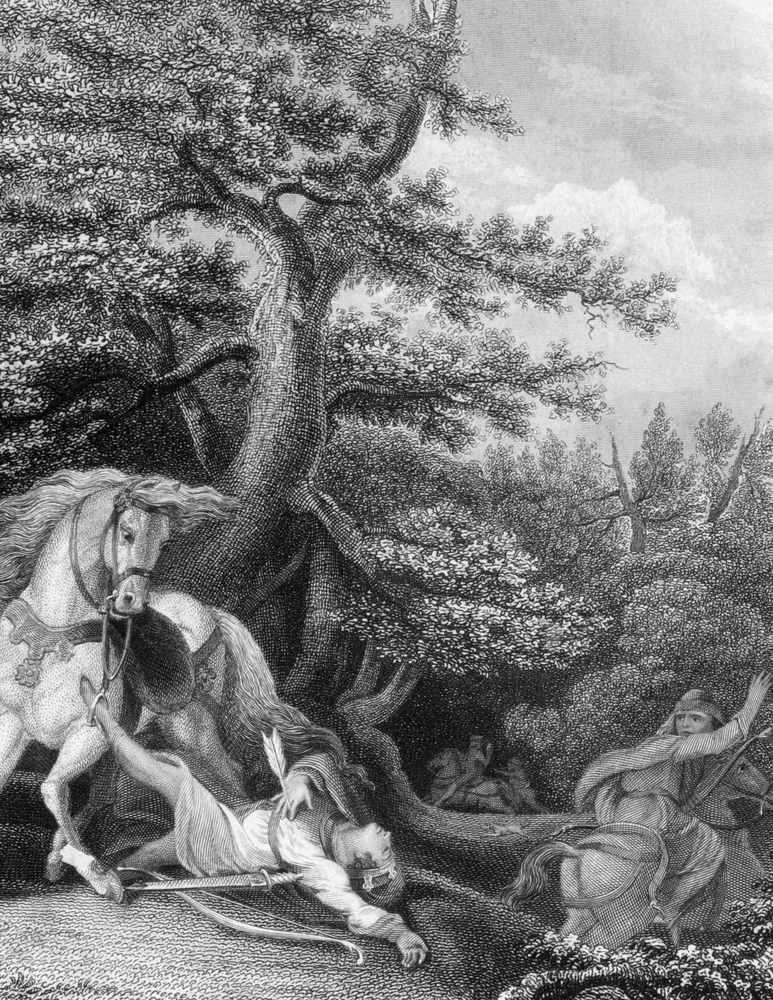

When delving into history and learning about the New Forest, it is inevitable that some of the characters from these commoning families will pop up to present themselves. Sometimes these are people who have done something so extraordinary that their deeds have been recorded for posterity, often reaching a certain level of fame. An example of this is the story of one member of the Purkis family who, according to legend, carried the body of King William II, or Rufus the Red as he was also known, to Winchester after he was killed while hunting in the New Forest in 1100AD. It’s difficult to read anything about the ‘accident or murder conundrum’ of the Red King without learning about Purkis’s involvement in the drama. However, more generally, as I am going about my research into the Forest’s history the names of commoning families repeat in less dramatic but no less significant ways. This could be in the annual accounts of one of the landed estates in or around the Forest, in contemporary newspapers and magazines, the court petty sessions or marked on many of the war memorials that can be found on village greens throughout the New Forest. So, next time you are in the Forest and enjoying the spectacular views, or admiring its wildlife and free roaming animals, spare a thought for the families of the commoners who have been making this possible for generations.

The body of King William I (Rufus the Red) was carried from the New Forest by a commoner.

You must be logged in to post a comment.