In the summer of 1709 boats packed with refugees began to arrive in England. These ‘Poor Palatines’, as they became known, were the first of over 10,000 Germans to arrive between May and November of that year. Displaced by war, the destruction of their homes, and suffering frequent incursions and pillaging by the French army in their native region of the Rhenish Palatinate, many of them had been forced to flee for their lives. Their situation was made worse by famine, caused by a series of failed harvests and severe winter weather, which meant that most of the refugees arrived in England in a state of near starvation, with the majority in very poor health.

Blessing in disguise

Many English people saw this influx of immigrants as a blessing in disguise. There had been widespread concerns that the population of England had still not sufficiently recovered from the devastating losses caused by the recurrences of bubonic ‘Black Death’ and Great Plague outbreaks, the last of which had occurred in 1665-1666 (although the threat of pneumonic plague continued well into the 1700’s). Prior to the refugee crisis of 1709, immigration had been proposed as a solution for increasing the population and an act of parliament had even been passed giving foreign protestants ‘the privilege of naturalisation for the fee of one shilling.’ It was generally believed that a larger population would expand the economy and wealth of England.

Townships in the New Forest

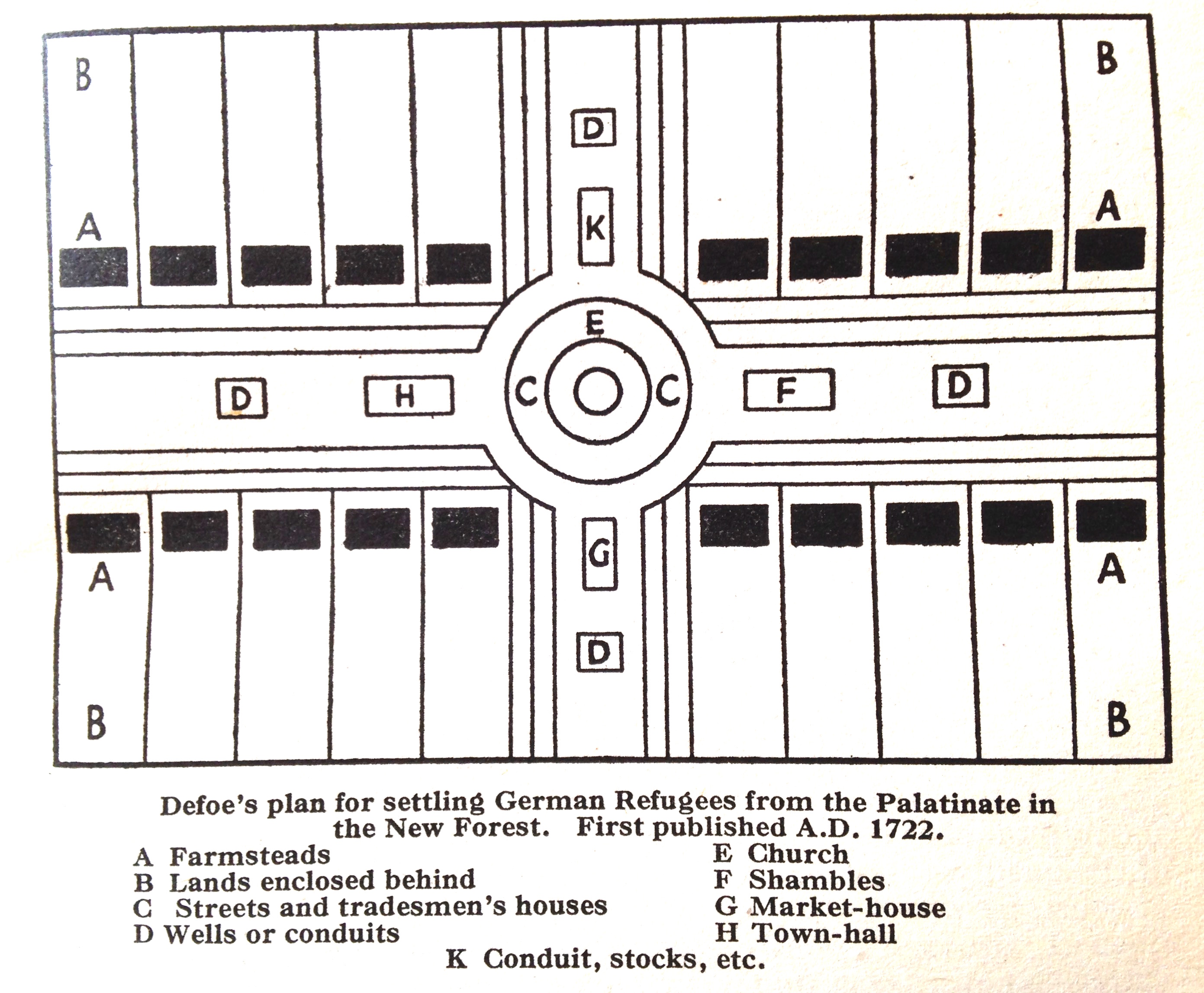

In consequence to the arrival of the Palatines Daniel Defoe author, economist and social commentator, suggested: “That the Palatine Strangers may be planted in small Townships, like little Colonies, in the several Forrests and Wastes of England, where the Lands being rich and good, will upon their Application to Husbandry, and Cultivation of the Ground, soon not subsist them, but encourage them….” * One of the areas earmarked for such cultivation was the New Forest. In his scheme to turn the New Forest into a model township 4,000 acres of land were to be divided among the ‘best’ twenty families, who were to be freed of rent and taxes for twenty years. The families were also to be advanced £200 each in ready money to set them up with the purchase of tools, animals, seed, and other equipment. (The area selected for this model settlement is believed to have been near Lyndhurst.) Not only did Defoe want to ‘cultivate all of the nation’s land to the last square foot’ but he thought that his idea ‘offered an opportunity to conqueror some of the wastes [commons] that blighted the face of England’.

Disperal of the ‘Poor Palatines’

So serious was this idea considered that the Board of Trade sought opinion from the Attorney and Solicitor General about how to implement the plan. To set things right with the commoner’s of the New Forest it was suggested that they could be bought off by the establishment of a Court of Claims, which would compensate their losses, or be given allotments in the new settlements. In the end the scheme never amounted to anything. The Government simply couldn’t afford it. Unfortunate as it was for the refugees, the New Forest was thankfully saved. The initial outpouring of national sympathy and charitable donations that provided relief to the many thousands of refugees soon dwindled. Political buck-passing quickly broke out, as did ‘unchristian’ incidents of xenophobia towards the refugees. Desperate steps were taken to disperse the ‘Poor Palatines’ either by sending thousands of them to the colonies, including Australia, Jamaica and America, by imposing them on the country’s parishes or forcing them home. With the refugees all settled elsewhere the Foreign and Protestants Naturalization Act 1708 was later repealed.

Defoe’s plan as illustrated in ‘The Commoners’ New Forest’, F.E.Kenchington, 1944.

*A similar, though less ambitious, plan to settle the Palatines in the royal forests and wastes was suggested to the earl of Sunderland, by the council of trade and plantations, Whitehall, 1 June I709.

You must be logged in to post a comment.