The statue of King Richard I – the Lionheart – great-great-grandson of William the Conqueror stands outside the Houses of Parliament.

If you had lived in England on this day (16 October) 958 years ago chances are you would be aware that a momentous battle had just been fought, only a few days earlier, near Hastings in Sussex. Even if you didn’t know the exact details you would undoubtedly know that the English king, Harold Godwinson, had been slain. How would this affect you? To begin with, probably not a lot. But the victor of the battle, Duke William II of Normandy, later to be known as William the Conqueror and then King William I, would fundamentally change what it was to be ‘English’ during his twenty-year reign. Even today the result of these radical changes are still in evidence but have become so familiar to us that they even form part of our national identity.

Raiders and pirates

The Normans were descended from the Norse (Norseman became Northman or Norman) who were raiders and pirates from the Scandinavian and Nordic regions. They settled in the region of France that became known as Normandy, establishing a powerful dynasty that included William the Conqueror. Prior to the Norman Conquest, if you were a man you might possibly have had a name such as Eadwine, Æthelred, or Gyrth, or if you were a woman, Ælfgifu, Ealdgyth or Cyneburh. After 1066 Anglo-Saxon names became synonymous with defeat and so children were given Norman names, such as William, Robert, and Henry or Alice, Jeanne, and Margaret, to better assimilate them into society. These names seem so familiar to us now and, somehow, more English. From the time of the Conquest Norman-French began to influence the English language, customs and culture in a way that has stayed with us ever since.

Nova Foresta

William I also imported his passion for hunting, for which he created the Nova Foresta in 1079. To protect the beasts of the chase and their habitat, he introduced Forest Law and with it an administrative and legal system that can still be witnessed in the New Forest today, in the form of the Verderers’ Court at Lyndhurst. ‘Verderer’ is derived from the French word for ‘green’ and signifies the area of responsibility for these powerful Forest officials. The first mention in written record of the New Forest occurs in the Domesday Book (Great Survey), to which a whole section is devoted. No other area of the country has this privilege. The Domesday Book is our oldest public record, which was commissioned by William I to inform him of his fiscal dues, and the taxes he could expect to receive from around the country. The Domesday Book remains an effective legal proof of land ownership.

The Queen Wills It

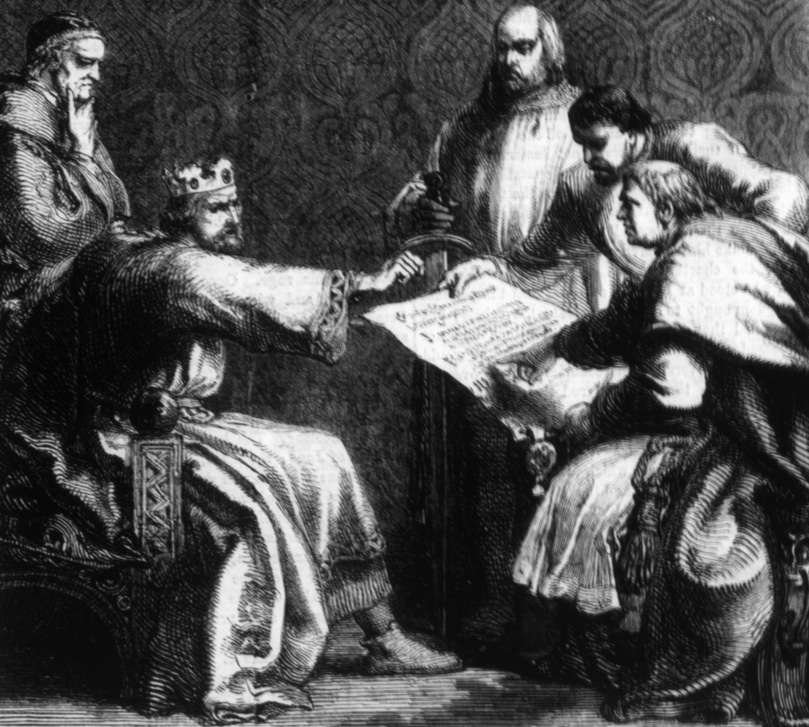

Even today Norman-French is used during the passage of Government Acts through the Houses of Parliament with phrases such as, “La Reyne le vault” (The Queen wills it.). This is because William I, and his royal descendants, bestowed and upheld the basis of English law and the institutions that eventually developed into Parliament. Richard the Lionheart, whose statue is outside the Houses of Parliament, as a patriotic symbol of our nation’s virtue and virility, is the great-great-grandson of William I. He didn’t even speak a word of English. His brother, John, is regarded as the worst king of England (even worse than Rufus the Red, and that’s saying something) but through his negligence and mismanagement Magna Carta Libertatum – better known as Magna Carta – was born (in 1215). For the first time in history an English monarch agreed in writing to safeguard the rights, privileges and liberties of certain of his subjects, such as clergymen and nobles. This legal document has inspired other forms of contract between rulers and citizenry, such as the United States Constitution, and has consequently made British law the envy of the world.

Magna Carta to Forest Charter

In 1217, two years after Magna Carta was issued, the Carta de Foresta or Charter of the Forest became law. Whereas Magna Carta established rights for the barons, the Charter of the Forest gave real rights and freedoms to ordinary citizens. It is often known as the ‘Commoners Charter’ because it relaxed some of the extremes of Forest Law, such as the death penalty or mutilation for killing a deer and made provision for the economic protection of free men, who depended upon the Forest to graze their stock and utilise many of its natural resources. The Charter of the Forest codified local law and customs, which was much more practical to ordinary people. Because of this the Commoners Charter was in use for over 800 years. In fact, the last vestiges of the Charter were repealed only in 1971 by the ‘Wild Creatures and Forest Laws Act’. Section 1(1) abolished ‘(a) any prerogative right of Her Majesty to wild creatures (except royal fish and swans), together with any prerogative right to set aside land or water for the breeding, support or taking of wild creatures; and (b) any franchises of forest, free chase, park or free warren. Thus, it was not until the twentieth century that William I’s medieval forest law was effectively ended.

Magna Carta Libertatum – for the first time in history an English monarch agreed in writing to safeguard the rights, privileges and liberties of certain of his subjects, such as clergymen and nobles.

You must be logged in to post a comment.