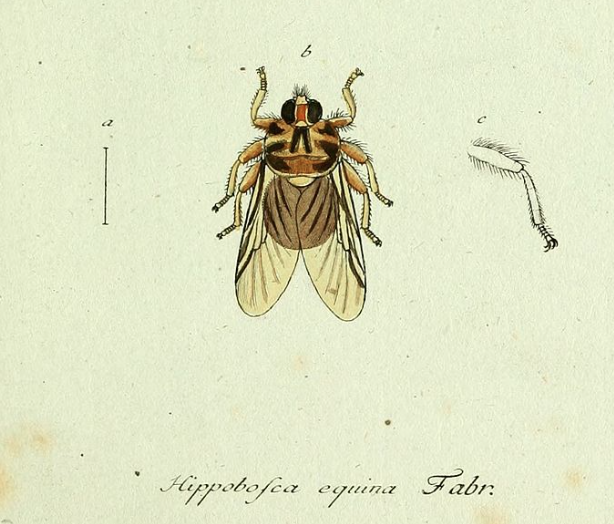

Forest fly (Hippobosca equine) a pesky resident of the New Forest. (Image #1. Dated 1793.)

In 1895 a local newspaper published ‘Notes on Injurious Insects’.[1] Chief among these perilous mini-beasts was the forest fly (Hippobosca equina) aka horse louse fly, side-fly, or crab-fly, a bloodsucking pest that ‘causes great annoyance to the horses in the New Forest of Hampshire’.[2] In the summer months, generally between May to October, this parasitic insect preys upon the resident free-roaming New Forest ponies and any visiting horses. It has also been known to feast on Forest cattle. (I’ve even found them on my dogs, in the house. Though the dogs probably carried them in unawares.) The forest fly measures approximately 10mm in length with a wingspan of about 8mm and is variously described as reddish brown to blackish chestnut in colour, with yellow or white spots on its abdomen. Once it has found a suitable host, unless it is disturbed and flies off, or is killed, it will basically stay put for as long as it can. The forest fly is notoriously hard to squash, due to the seemingly armour plating of its body, and must be virtually eviscerated to destroy it.

The forest fly does not store the blood it sucks from its host, which means that it must feed regularly. It is the manner of the fly’s sideways movement across the animal’s body, however, that is much more upsetting to its host than its bite. These tenacious little devils cling on determinedly to their unfortunate hosts and travel, as one observer describes, by ‘making tracks under the ponies coat like a deer wandering through a field of corn’. At the end of each of its six legs are claws that resemble grappling hooks and it is with these that the fly applies a tenacious hold, as it creeps through the hairs of its unfortunate host. Its favourite place to congregate is on the horse’s perineum and additionally, if a mare, the udders or, if a gelding, on the sheath, where there are less hairs and less chance of being dislodged. As you can imagine this can cause indescribable distress and alarm to animals not habituated to such ticklish impertinences!

Stories of panic and distress

As the Victorian newspaper further reported, ‘the method of attack is really irritating to the animals, and in the cases of horses unaccustomed to it, especially, is really a source of serious danger to those in charge of the infuriated victims’.[3] Therein lies the trouble. Good-mannered horses that are otherwise sweetly behaved, trustworthy, and obedient, when at home, can suddenly turn into bucking broncos or demonic savage beasts if a forest fly lands on them when being ridden on the New Forest. I have heard tales of visiting horses being brought to the New Forest driven half mad with terror by the sensation, and normally quiet animals being rendered unrideable. Stories are even told of times past when New Forest ponies, used for transport to other areas, would inadvertently carry the flies away with them. As the flies moved onto the town animals all pandemonium would ensue, with the horses harnessed to tradesman’s vans, milk carts and drays bucking or bolting and causing widespread panic. I once, inadvertently, closed my pony inside the horsebox with a crab fly on him, after a lovely ride on the Forest. He kicked the sides of the box in violent protest as we travelled, all the way home.) The ponies born on the Forest or those turned out to roam the heaths and woods, however, become inured to the insect and generally accept their presence with resignation, if not toleration, making them the ideal mounts or driven animals for people regularly using the New Forest.

Treatments and stratagems

George Samouelle, the celebrated nineteenth century entomologist, writing about Hippobosca equina in 1819 declared, “In the New Forest of Hampshire they abound in the most astonishing degree. I have obtained from the flanks of one horse six handfuls, which consisted of upwards of 100 specimens.”[4] The good news is, however, that the forest fly is found only in the New Forest and, though it may land on you, humans are not generally on its dinner menu. (Naughty Forest boys were said to collect them to put the clinging-critters in girls’ hair as a prank.) For centuries people have been trying to find protection against this dreaded insect and there are some recommended strategies for reducing the risks of forest fly attacks on horses or ponies but none are 100% guaranteed effective. In 1844, one such treatment involved taking ‘mineral earth 8 oz., and of lard 1 lb., and make them into a salve. Some of this salve is to be spread on here and there upon the hair, and worked in with a wisp of straw. After 24 hours the salve is to be washed off with warm water, in which brown soap has been dissolved.’[5] Unfortunately, there is no follow-up to confirm the efficacy of this concoction.

Towards the end of the nineteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth century chemicals were being employed whereby….‘horses may be protected for a few hours by rubbing a paraffin rag over them, a very advisable thing to do in the New Forest, for a horse fresh in the locality when being driven, for pro tem. This undoubtedly keeps off those pertinacious and annoying Forest Flies.'[6] Modern day approaches also include the use of chemical spray repellents that are much more suitable as topical treatments; fly-rugs, and the liberal application of ointments, such as Vaseline or Sudocrem, on the areas of the horse where the flies congregate are also used. The flies are most active in the middle of the day and so early morning or early evening rides across the Forest are the best times to avoid these tenacious little critters. Combining stratagems may go some way to reducing the risk of experiencing a forest fly attack and a possible impromptu rodeo too!

A close-up of a New Forest fly showing the grappling-hook-like feet.

FOOTNOTES:

[1] The Hampshire Advertiser (Southampton, England), Wednesday, May 29, 1895; pg. 4; Issue 5109. 19th Century British Library Newspapers: Part II.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Georges Samouelle, The Entomologist’s Useful Compendium: Or, an Introduction to the Knowledge of British Insects (London, 1819), pp. 302-303

[5] Henry Stephens, The Book of the Farm, Vol. 3: Summer & Autumn, British and Irish History, 1844 (Cambridge, 2010), pp. 855-856.

[6] Frederick Vincent Theobald, Reports on Economic Zoology for the Year Ending 1902 (Kent, 1902), p. 147.

IMAGES:

#1: Forest fly (Hippobosca equina) dated 1793.

#2: Forest fly (Hippobosca equina) close-up.

You must be logged in to post a comment.