Legend tells of horses escaping from sinking Spanish ships of the Armada swimming to shore to establish the herds of wild New Forest ponies.

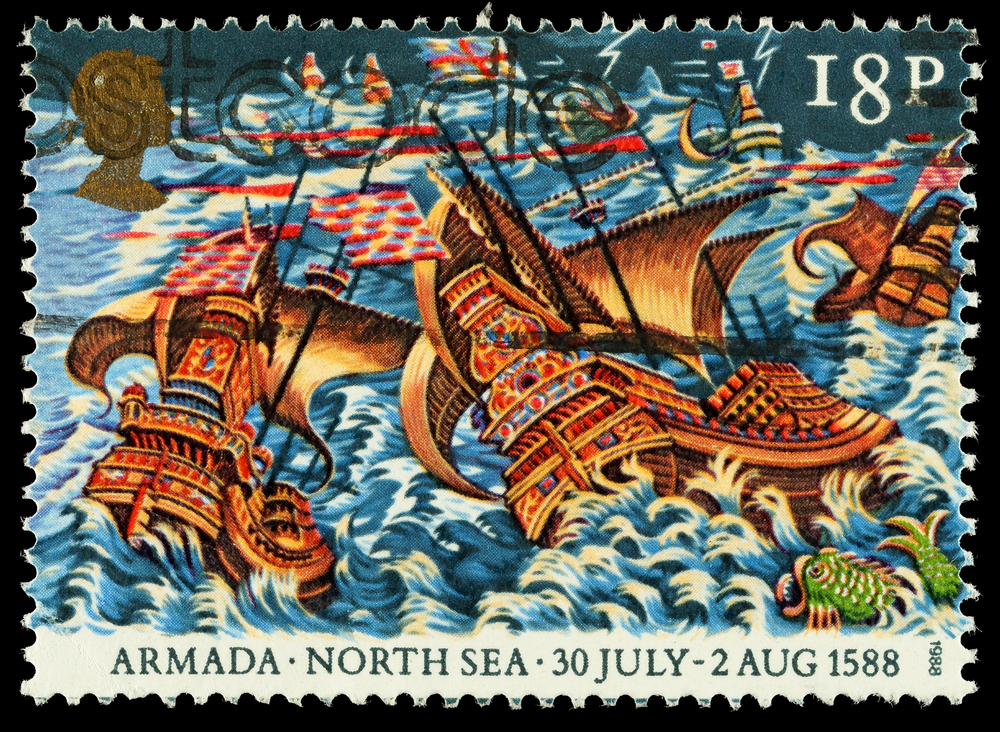

In August 1588 Queen Elizabeth I delivered one of the most famous speeches of her reign in which she is said to have declared; ‘I know I have the body of a weak, feeble woman; but I have the heart and stomach of a king, and of a king of England too, and think foul scorn that Parma or Spain, or any prince of Europe, should dare to invade the borders of my realm.’ The invasion she was referring to, of course, was that of the Spanish Armada. However, by the time the speech had roused the land forces she was addressing in Tilbury the threat from Spain was largely spent. A battle near Calais had routed the 130 ships of the armada and their commanders were desperately trying to return home. They had to sail around the northwest tip of Scotland because the English fleet had control of the English Channel and were effectively blocking their retreat and the quickest way home. The Spanish ships had no ammunition left to fight their way through and were forced to take the long way round.

The legend of escaping horses

Legend has it that during this time many horses escaped from sinking Spanish ships and swam ashore to establish the herds of wild ponies that roam the New Forest today. Other native breeds have also claimed the same descent. The Shetland pony in Scotland is said to have bred with shipwrecked horses from the Spanish Armada flagship, the Gran Grifton, which foundered off the coast of Fair Isle; and the Irish Connemara pony claims descent from escaping Andalusian stallions mixing with local mares. Unfortunately as romantic as it sounds the truth is far less than idealistic.

The disposal of horses and mules

The majority of the armada was intact when it arrived in the North Sea but the ships had not been equipped with the provisions required for such a long sea voyage and they quickly became short of food and water. The fleet commander, Medina Sidonia, ordered all the horses and mules to be thrown overboard to save the available rations. The pursuing English ships passed the poor animals in the sea. In some reports forty horses and forty mules were jettisoned and in others hundreds of dead and still swimming animals were seen, but too far out to sea to have any hope of reaching the shore alive. Horses transported by sea during this period would arrive at their destination in a very poor state, particularly after long voyages. They would be dehydrated from lack of water, sickened from the constant pitching and rolling of the ship, and horribly malnourished or starved from a lack of food or appetite. Horses in this condition would hardly be able to stand let alone swim any distance.

The armada is wrecked

When the armada reached the Herbrides it was battered by unseasonably hostile weather. The ships were not built for sailing in such treacherous waters and the Spanish captains had no charts or maps with which to navigate. Medina Sidonia’s directions for the route home had been vague in the extreme. Fifty percent of the ships were lost as they tried to sail the northwest tip of Scotland and down past the west coast of Ireland. Thousands of men lost their lives as their ships sank or were wrecked.

Animal survivors

Stories of animal survivors persist though, and there are tales of other animals swimming ashore to establish descendants in the British Isles including chickens, cats and dogs. The West Highland terrier, for example, is alleged to have been established by a Spanish breed of small dog kept on board the ships to hunt rats. Most historians have now cast doubt though upon any horses reaching British shores. Interestingly, a genetic study in 1998 suggested that the New Forest pony has ancient shared ancestry with two endangered Spanish pony breeds, the Asturcón and Pottok. This heritage would have begun long before the Spanish Armada but possibly during another notable invasion of Britain, that of the ancient Romans.

You must be logged in to post a comment.